Today’s post comes to you courtesy of Matthieu Castillo, a dedicated English Literature student, currently serving as a library intern at the Wolfsonian—FIU. Matthieu hopes to become an academic librarian and desires to promote equity in school curricula and higher education. His persistent dedication is fueled by an intense commitment to advocate for diversity and inclusiveness in educational settings. In the process of accessioning some ephemeral materials in our rare book and special collections library, he encountered some items depicting Emperor Ménélik II of Ethiopia. Matthieu became interested in the very different depictions of the leader created in the wake of his successful defense of his nation during the First Italo-Ethiopian War (1895-1896). Here is his report:

Emperor Ménélik II (1844-1913) is remembered as a heroic figure in his homeland, a leader whose resistance echoes through the annals of Ethiopian history. He is an embodiment of national resilience and pride for his leadership during the First Italo-Ethiopian War. Emperor Ménélik II led his country to victory against Italian forces during the Battle of Adwa (1896) when Italy first attempted to conquer and colonize the region. Ménélik made Ethiopia the first African country to successfully resist European colonization. The Treaty of Addis Ababa, (or New Flower), affirmed Ethiopia’s independence on October 23rd, 1986, and ended the First Italo-Ethiopian War. March 2nd is celebrated annually as Adwa Victory Day to commemorate Ethiopia’s victory in 1896.

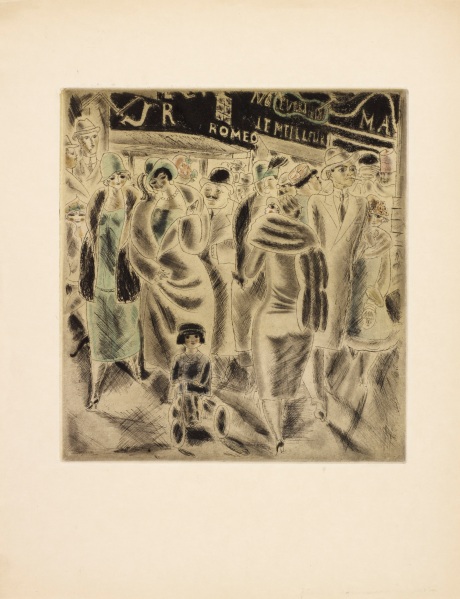

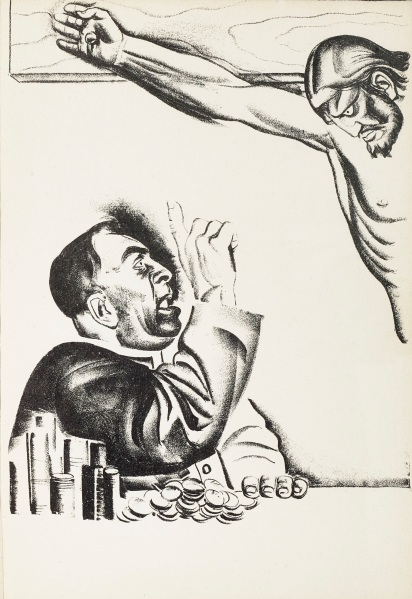

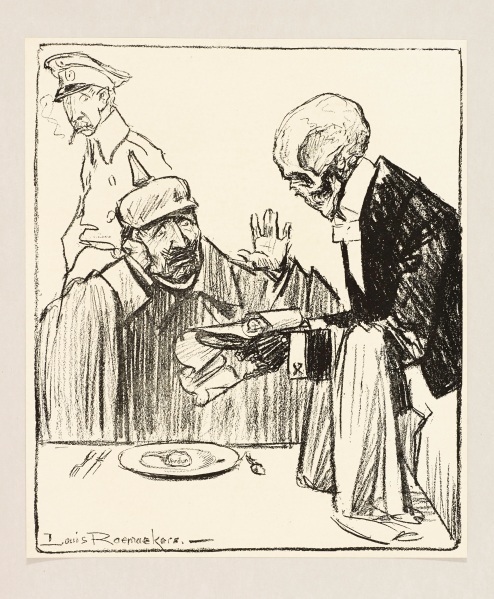

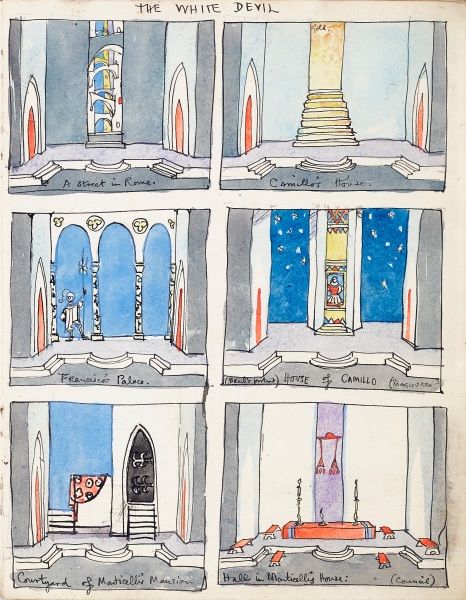

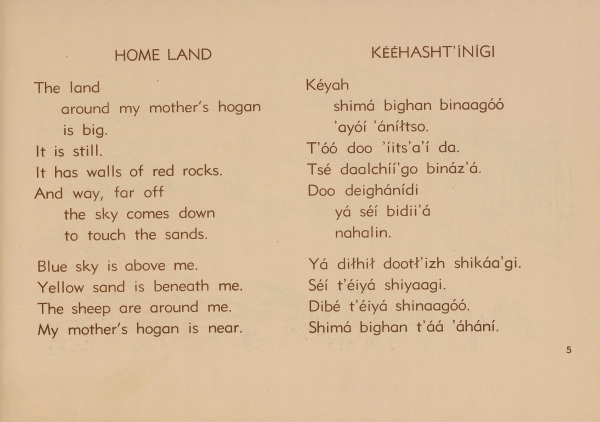

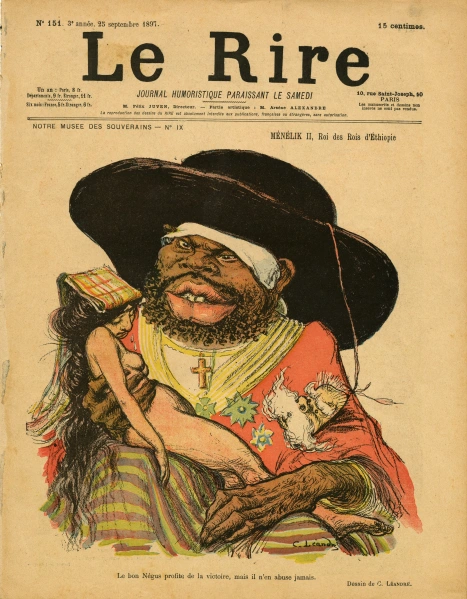

Le Rire magazine cover with caricature of Emperor Ménélik II (1844-1913)

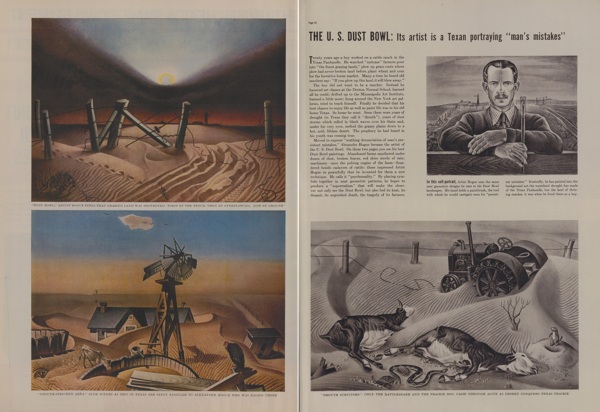

The French magazine Le Rire [Laughter] (1894–1971) used humor in its social and cultural commentary. It aimed to draw readers into a world where real-life events and social discourse intersected. Le Rire adopted an absurdist point of view and used vibrant images and caricatures to spread awareness of the political climate surrounding contemporary global affairs.

In 1897, Le Rire reported Emperor Ménélik II’s defeat of the Italian army. This is an example of how Le Rire involved themselves in international affairs, using their magazine as a resource for information. In this issue, Emperor Ménélik is depicted as a powerful creature, with an exposed Italian woman in his grasp. Italian Prime Minister Francesco Crispi’s decapitated head lies tucked in Ménélik’s arm, tied to a string, and hanging like a somber victory trophy. It symbolizes the fall of the Crispi’s government in 1896 following defeat in the war. With a crucifix draped on his chest to represent his Christian faith, Ménélik is portrayed as “the king of kings” with a caption that emphasizes his role: “The good Négus benefits from victory, but he never abuses it.” Calling Ménélik the king of kings highlights his power and lauds his merciful qualities. The visual prominence of crucifix around his neck implies moral superiority. According to this interpretation, Ménélik is a devoted Christian and moral ruler.

On the other hand, this description can be interpreted as a warning. Le Rire might be critical of Emperor Ménélik’s governance. It could be satirical to refer to him as a good Négus who gains from victory, suggesting irony over his image of virtue. It could raise doubts about whether his acts are truly genuine by suggesting a difference between his Christian status and potentially “barbarous” behaviors. It is possible to see Ménélik’s idea of enjoying victory without abusing it as a critique of the dynamics of power relationships and its susceptibility to abuse, therefore discrediting his alleged moral superiority.

The caricature’s creator, Charles Léandre, used stereotyped features to portray Emperor Ménélik. Another interpretation could be that Ménélik reflects the biases that were popular during this era. While Léandre is seemingly congratulating Ménélik on his victory over France’s colonial rival, the unflattering depiction Ménélik still embodies the reigning ideals of European colonialism. The characterization of Ménélik as a monster with abnormal facial features tends to reinforce colonial justifications based on white supremacy. The racist judgment that Africans are “savage and barbaric” is confirmed through this image. Having Crispi’s head suspended from his hat symbolizes the shame and loss that the Italian government faced as an aftermath of their failed conquest, but also implicitly transforms the Christian king into a savage “headhunter.”

One final approach could be that Le Rire could simply be admiring Ménélik. The caricature is purposeful, adhering to the satirical elements that Le Rire has in place. This depiction appears to illustrate what happens when European audiences are unfamiliar with African culture. This lack of understanding, however, does not justify the use of racist parody art. Other depictions of the emperor include political circumstances while avoiding racial stereotypes.

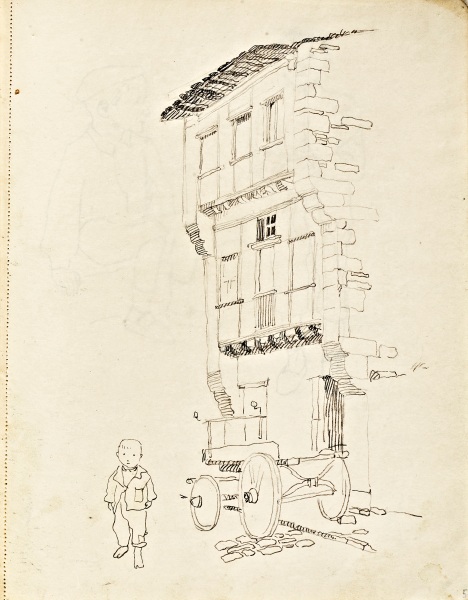

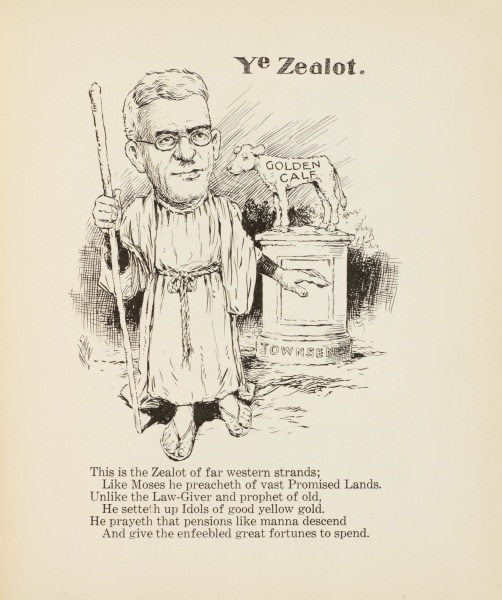

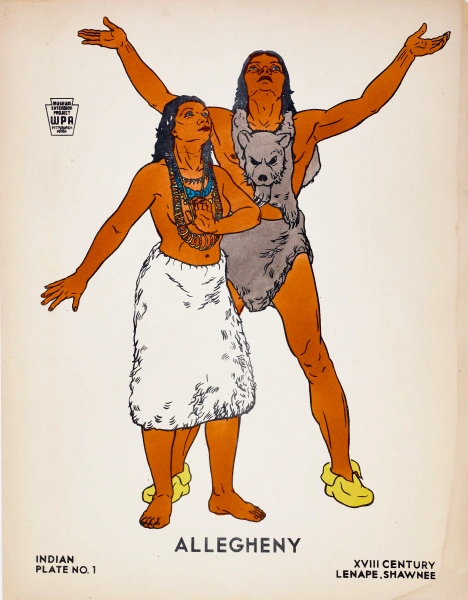

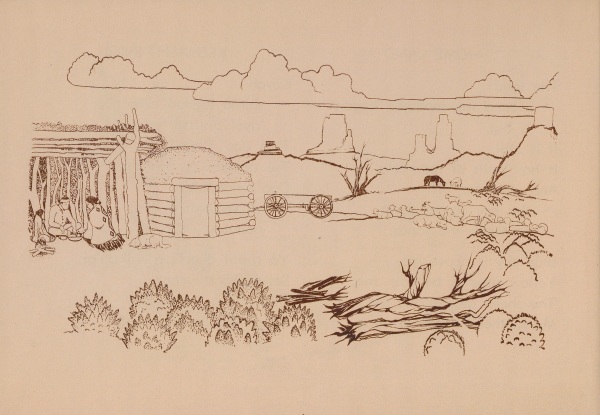

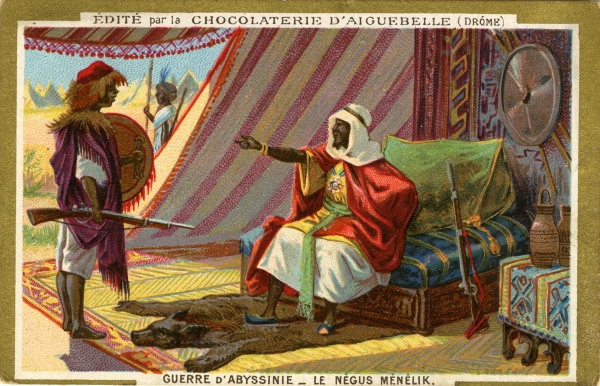

Abynissinan War – The Négus Ménélik. P. Chocolaterie D’Aiguebelle.

Chocolaterie D’Aiguebelle, (a French chocolate factory originally founded by Trappist monks from the abbey Notre-Dame d’Aigubelle, France), depicts Emperor Ménélik in a noble and respectful manner. As a promotional gimmick, the chocolate firm paired their chocolate bars with collecting cards to broaden public awareness on worldwide issues. This specific card includes a portrait of Emperor Ménélik. Like Le Rire, the Chocolaterie d’Aiguebelle praises his successful reign but does not use racist caricature in the process. Rather, the emperor is depicted as sitting on a throne, signifying his position as a sovereign. With a gun at his side, he directs and leads his troops in preparation for the conflict between Italy and Ethiopia. Emperor Ménélik is represented in this image as a ruler rather than a monster, and his clothing serves as a visual cue of his royalty. Ménélik wears more opulent and attractive clothes than the warrior entering his tent, indicating their differences in status.

The collecting cards produced by Chocolaterie D’Aiguebelle demonstrate that it was possible to depict African leaders—like Emperor Ménélik—in an acceptable artistic style and without resorting to racist ridicule. Even though Le Rire‘s first impulse was to celebrate the emperor for his victory, the decapitated head of Franscico Crispi, whose administration went to disgrace with him, serves as an example of how Le Rire depicts Emperor Ménélik as a monster, outside of the barbaric features itself. The chocolate firm pays tribute to Ménélik in a non-offensive manner, depicting him as the king that he truly was.

Ultimately, Emperor Ménélik II is revealed to be a man of morals, in contrast to Le Rire’s “barbarous” depiction of him. He protected Italian officers and punished underlings who killed or mistreated prisoners. His dedication to extending mercy to those who invaded his land demonstrates his generosity and integrity. Ménélik deserves to live on as the hero and monarch that he was, his role of mercy and leadership recognized for all time.