Behind the Scenes of a Wolfsonian Library Installation Examining the Dust Bowl

This past fall 2023 semester, I taught a Florida International University undergraduate history class titled America & Movies: Between the Wars, 1919-1939. Covering the eras of “Roaring Twenties” and “Depression Decade,” the students in the class viewed films made during or about the period and compared them to the historical reality as reflected in primary and secondary source materials and the stories that could be teased out of Wolfsonian museum artifacts. In lieu of the final paper project, six students chose instead to curate a library installation that opened just after the semester closed. Amal Albaladejo, George Lee, Dwayne Krier, Valentina Berrio, Sophia Medina, and Carlos Manuel Bleiker Morcillo spent numerous Saturday afternoons at The Wolfsonian Library looking over and selecting items that might help to visually tell the story of the greatest man-made ecological crisis of the 20th century, the Dust Bowl, 1931-1939. After making an initial selection of materials came the hard work of researching each item and writing interpretive and descriptive texts in the compressed period of a couple of months. As the course was also designed to get them to deconstruct, critically analyze, and historicize films of the era, they were also tasked with choosing some film clips to accompany the artifacts and labels in the cases. Their collective efforts came to fruition last Friday as the student curators and public were invited to see the newly installed exhibition and to hear the students talk about the experience of putting the show together.

A lot of work goes on behind the scenes to put together an installation, involving numerous editors and the skilled labor of The Wolfsonian’s art handlers and exhibition installers.

For the student curators, perhaps the most painful part of the process was having to winnow down the pre-selected artifacts to choose only those essential to the story. Once the final cuts were made, the team laid out the items on paper templates of the cases to see what best fit and what juxtapositions helped reveal connections and transitions.

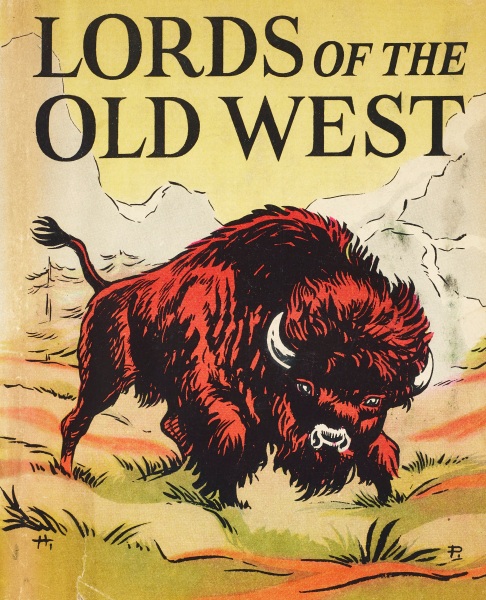

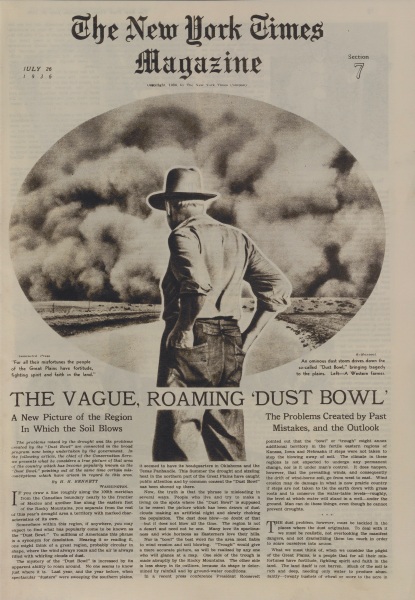

As the gallery space invites dividing the narrative structure into four sections, the student decided to focus on four: the period when scores of Plains Indian societies and millions of buffalo roamed the plains; the transformation of the grasslands into commercial wheat farms; the 1930s when Depression and drought forced millions from the region beset by dust storms or “black blizzards;” and finally, the Roosevelt Administration’s conservation programs designed to fix the human and ecological tragedy.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Christopher DeNoon Collection for the Study of New Deal Culture

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

The Wolfsonian–FIU, gifts of Francis Xavier Luca & Clara Helena Palacio Luca

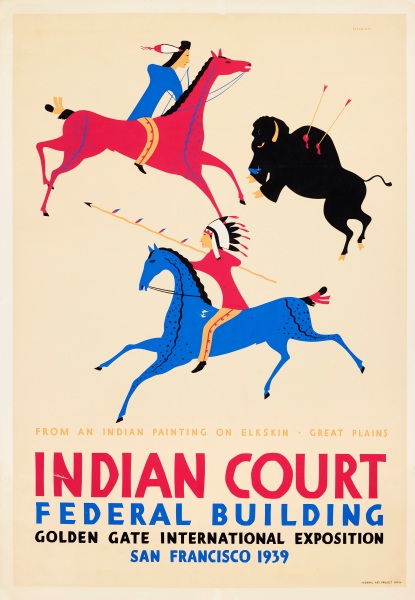

Over the course of selecting items for display, there are times when the exhibition space itself pushes some items from the can to the cannot be included list. This was the case with a poster and a painting that the students hoped to place on opposite sides of the exhibition space. The poster, Indian Court, Federal Building was designed by Louis Siegriest (American, 1899-1989), published by the Works Progress Administration, and exhibited at the San Francisco world’s fair of 1939-1940. After a decade of dealing with dust storms, this poster beckons back to a “pre-fall paradise,” celebrating Plain Indian culture by reproducing figures reminiscent of those drawn on buffalo hide teepees by the native peoples.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

In stark contrast to the patriotic palette used for the government-sponsored poster, the painting, Missouri Woman (1938) by Burr Singer (American, 1912-1992) forces the viewer to confront a care-worn woman in faded red, white, and blue clothes holding an empty flour sack and standing resignedly before a desert-like landscape and dark storm clouds.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

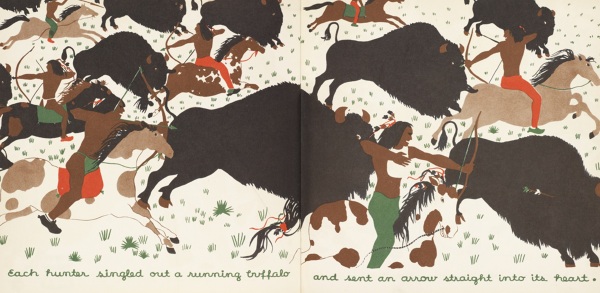

While a few items included in the first section date from the period when the transcontinental railroad brought homesteaders and speculative farmers into the region, most were created in the immediate wake of the Dust Bowl, when railroad companies and nature enthusiasts published nostalgic images of the grasslands, buffalo, and Plains Indian peoples to promote domestic tourism and a new ecological vision of the region’s future. One such item, Whistling-Two-Teeth and the Forty-Nine Buffalos (1939), a children’s book written and illustrated by Naomi Averill with the collaboration of naturalist Donald Peattie, includes color lithographs inspired by Native American paintings to depict their spiritual and harmonious relationship to the land and other creatures.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

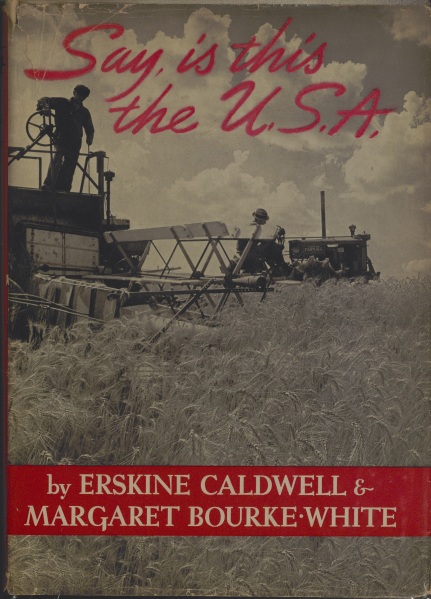

Before drought, overproduction, and poor farming techniques created the Dust Bowl crisis, most depictions of the region focused not on the native creatures and native peoples but on the farmers who believed that “the rain follows the plow,” and who were determined to transform the arid “desert” grasslands into America’s breadbasket. Railroad companies, land speculators, and the Homestead Act of 1862 encouraged American citizens to occupy and “improve” plots, even as industrial farming techniques and equipment plowed up lands ill-suited to monocropping. Photographer Margaret Bourke-White collaborated with author Erskine Caldwell to publish a pictorial biography of the U.S.A. in the 1930s, choosing an idyllic image of man and machine creating the bountiful harvests that made the Great Plains the nation’s breadbasket.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

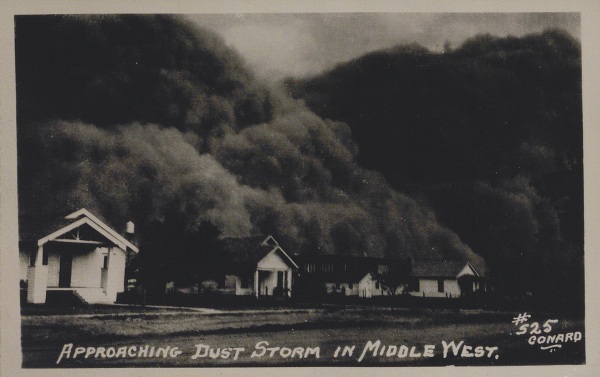

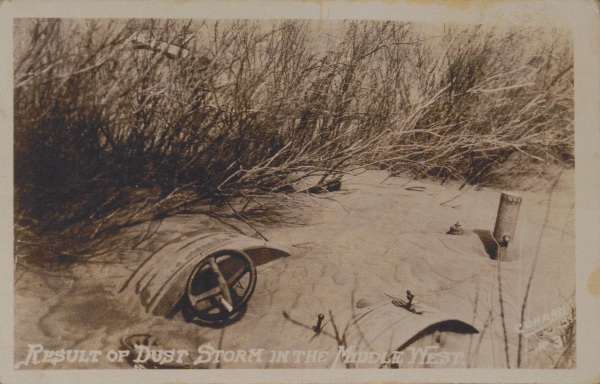

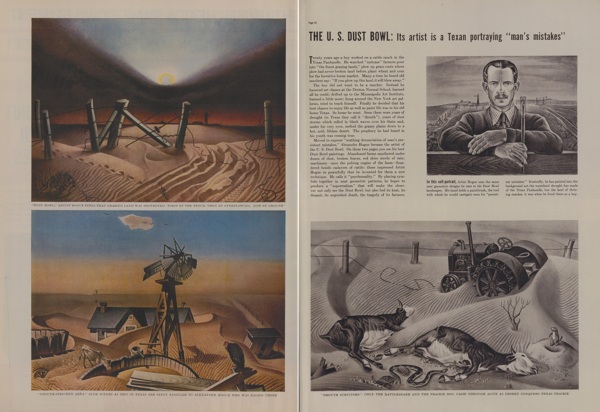

By the 1930s, most of the original three hundred million acres of wind-swept grasslands had been plowed under and planted with grain. Industrialized farming and overproduction, combined with the Plains’ natural drought cycle, brought disaster. Dust storms transformed farms into desert dunes, suffocated cattle, and sickened and killed farming folk with dust pneumonia. Photographers commissioned by President Franklin Roosevelt’s Resettlement and Farm Security Administrations documented the magnitude of the disaster while artists rendered prints and paintings to provoke public empathy for refugees.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, gifts of Francis Xavier Luca & Clara Helena Palacio Luca

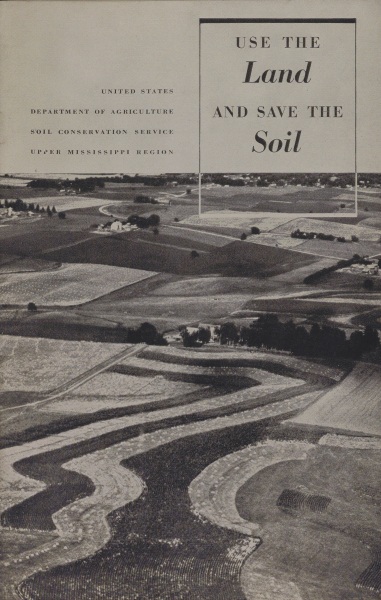

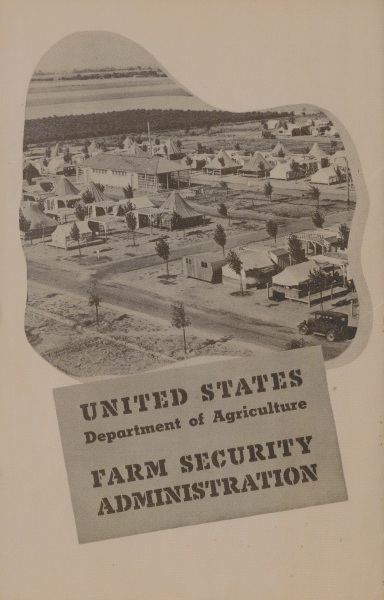

The Roosevelt Administration responded to the Dust Bowl crisis by introducing an alphabet soup of federal programs, including the Resettlement Administration (RA), Farm Security Administration (FSA), the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Soil Erosion Service (SES) and Soil Conservation Service (SCS). Abandoned lands deemed unfit for cultivation were seeded with drought-resistant grasses while RA and FSA employees set up sanitary relief camps in California for the Dust Bowl refugees.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, purchased with funds donated by Mitchell Wolfson, Jr.

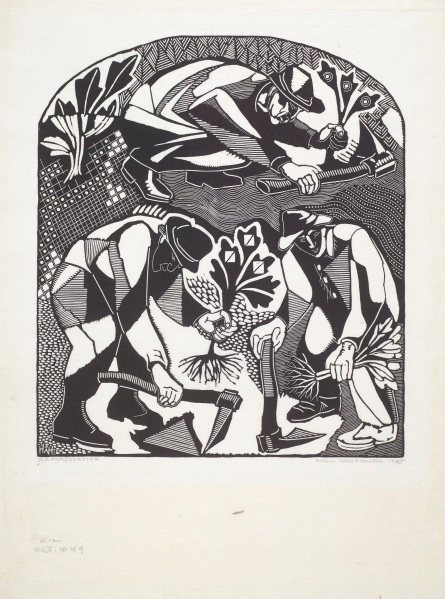

Farmers determined to cling to salvageable plots in the arid region were encouraged to adopt new cover crops, contour plowing, and terracing techniques to prevent soil erosion. CCC enrollees and SES and SCS workers planted billions of trees to hold down the topsoil and create shelterbelts and windbreaks. The programs began to pay off. Three years after Roosevelt signed the Soil Conservation Act into law in April 1935, soil erosion had dropped 65 percent, and by 1939, the worst of the storms had ceased. Helen West Heller, who produced at least 76 prints, paintings, and murals for the Federal Art Project (or FAP), created this woodcut print titled “Reforestation,” to celebrate the conservation work of Roosevelt’s “Tree Army” or CCC enrollees.

Print, Reforestation, 1935 / by Helen West Heller,

The Wolfsonian–FIU, The Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

A couple of experts, including Jeffrey Gold of the Living New Deal, showed up for the reception for the student curators and their families, and the students not only presented their installation but intelligently fielded the questions of the attendees.

The student curators’ installation will remain on view through February 11, 2024, so if the winds happen to blow you our way, do drop in.