A New Deal for the American Indian

In the final paragraph of the address he delivered at the Democratic National Convention on July 2, 1932, Democratic presidential candidate, Franklin Delano Roosevelt concluded his speech with the words: “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.” That promise of a “new deal” was taken up by his campaign, the press, the public, and later historians of the era to describe the wide scope of economic experiments, reforms, and alphabet-soup programs prescribed by FDR as remedies for the Great Depression. The federal government’s relations with Indian tribes would also undergo a radical departure from policies and practices that could be traced back to the earliest years of European colonization and the foundation of the American Republic. Although far from perfect and predictably paternalistic, the Roosevelt Administration’s dealings with the aboriginal peoples living on reservations in the United States most definitively constituted a “New Deal” for the Indian.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Promised gift

In the wake of two research visits by scholars respectively interested in the intellectual origins of the New Deal and the Work Progress Administration’s Index of American Design, I was inspired to reflect and focus on items in The Wolfsonian collection that document and define the new relationship forged between the federal government and Indian tribesmen. Collectively, these artifacts demonstrate how the New Dealers embraced a new economic ethos and cultural and religious pluralism that changed for the better the lives of Native American peoples.

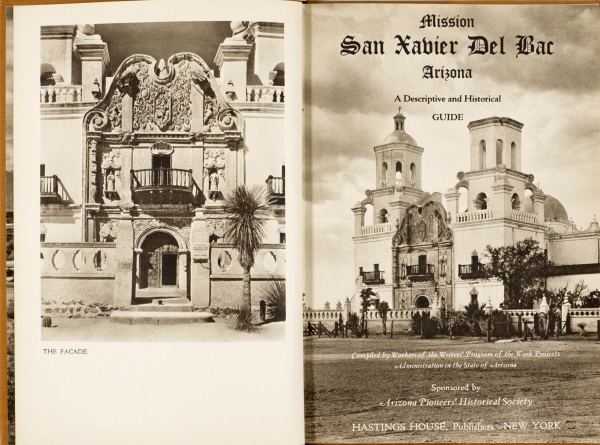

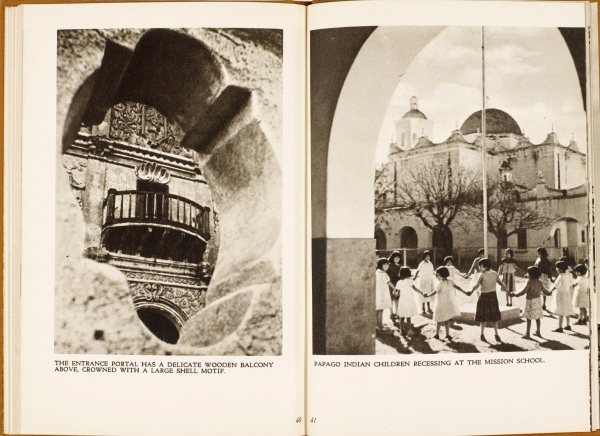

When Spanish conquistadors and colonizers first encountered the native peoples of the Americas, they vacillated between keeping them in separate repúblicas de indios under traditional indigenous leaders subject to royal authority versus Christianizing, assimilating, and integrating them into colonial society. A Works Progress Administration (WPA) guide to the San Xavier del Bac mission in Arizona, provided written and photographic descriptions of the historic edifice where Christian missionaries had been deployed on the fringes of the empire to transform “wild” Indians into “pacific” peons.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, gift of Christopher DeNoon

From the earliest days of the young Republic, too, presidential administrations oscillated between exclusion and “civilizing” policies, alternately negotiating land cessions and encouraging Indians to remove to the West, or coercing native peoples into assimilating into American society. Once the last of the proud and independent Plains Indian nations had been subdued and reduced to reservations as dependent wards of the state in the late nineteenth century, efforts continued to detribalize and “civilize” the natives. The Dawes Severalty Act was passed by Congress in 1887 with the aim of dissolving tribal entities and dividing communally-held tribal lands into small plots allotted to individual Indians. While leftover lands were made available to non-Indian citizens, the remaining natives were expected to become subsistence farmers even when economic realities, native cultural traditions, and the small, arid allotments they were settled on were ill-suited for success. Christian missionaries served as an unofficial arm of the federal government on reservations; in that capacity, they advocated removing Indian children from their families and shipping them off to remote boarding schools where they were stripped of their native tongue, traditional culture, clothing, and hairstyles.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Promised gift

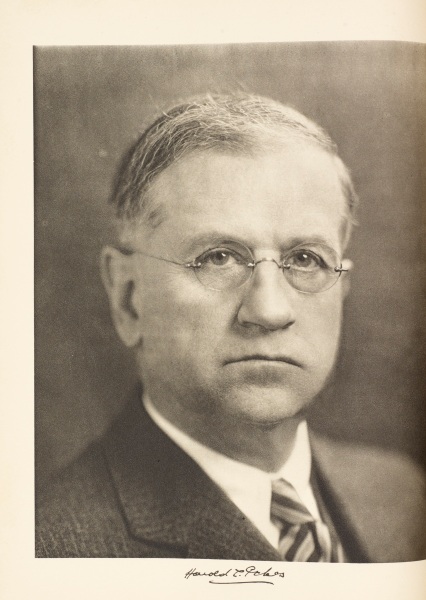

Under such combined pressures, by the 1920s the demographically dwindling and culturally disoriented reservation Indians were viewed by most American as a “vanishing race.” But they were not without sympathetic American champions. Chief among these was a Columbia University professor and “father of American anthropology,” Franz Boas, and his many students. One of those protégés, Lucy Kramer Cohen, would marry (and advise) Felix Cohen, the New Deal lawyer responsible for drawing up the legal frameworks of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. A decade before Franklin Roosevelt was elected president, an urban reformer named John Collier traveled to the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico, where he founded the American Indian Defense Association. This organization investigated and fought attempted encroachments on native land rights. Collier went further, criticizing even the Christian missionaries who attacked and forbade traditional native dances and ceremonies. Another champion of Navajo and Pueblo Indians, Anna Wilmarth Ickes published Mesa Land in 1933, even as her progressive Republican husband, Harold L. Ickes was tapped to serve as Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Interior.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, gift of Francis Xavier Luca & Clara Helena Palacio Luca

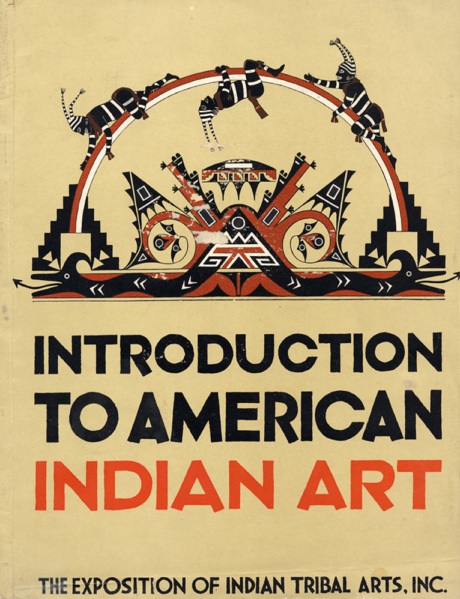

Attitudes towards Native American peoples and their cultural traditions were already undergoing a transformation even before President Franklin Roosevelt took office. In 1931, for example, an art opening in New York City showcased tribal art and material culture and boasted at being the “first exhibition of American Indian art selected entirely with consideration of esthetic value.”

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

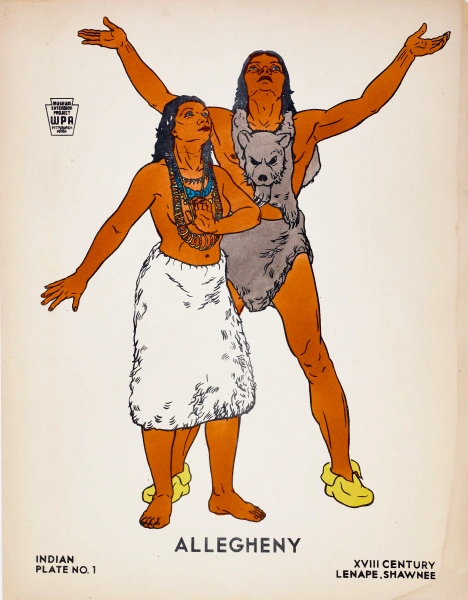

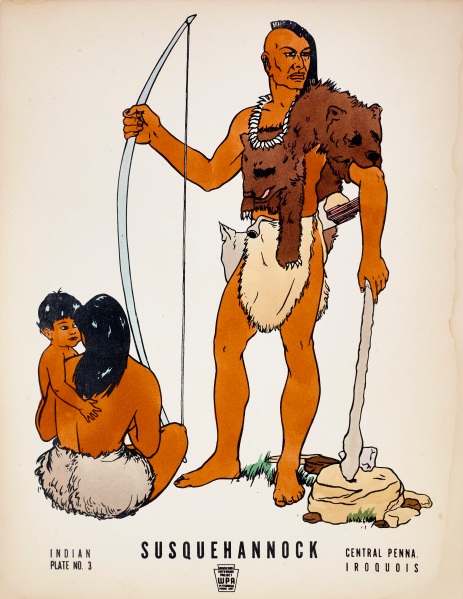

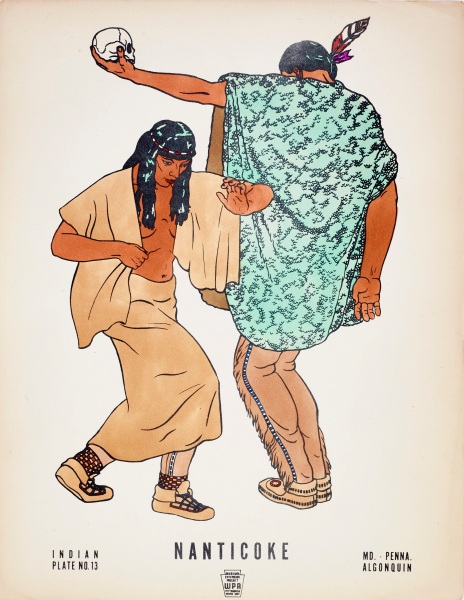

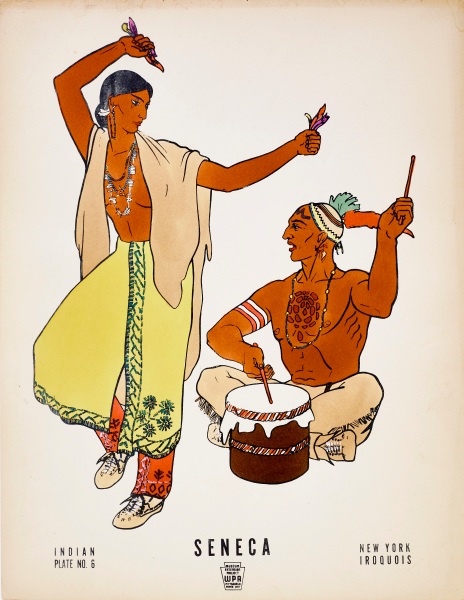

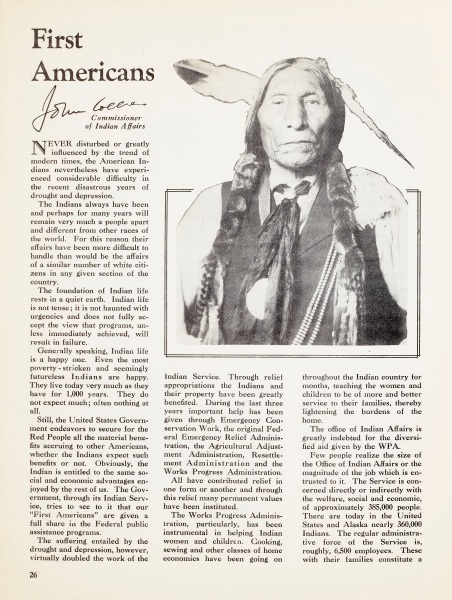

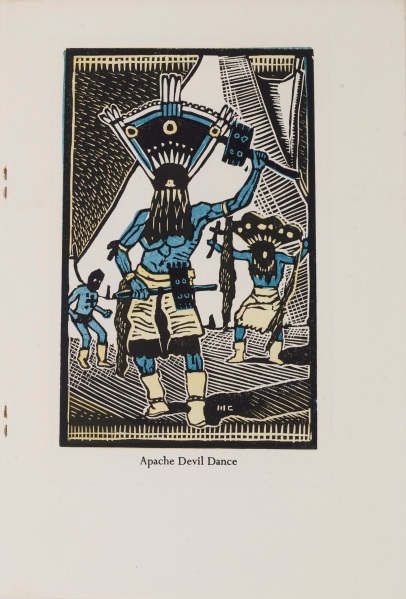

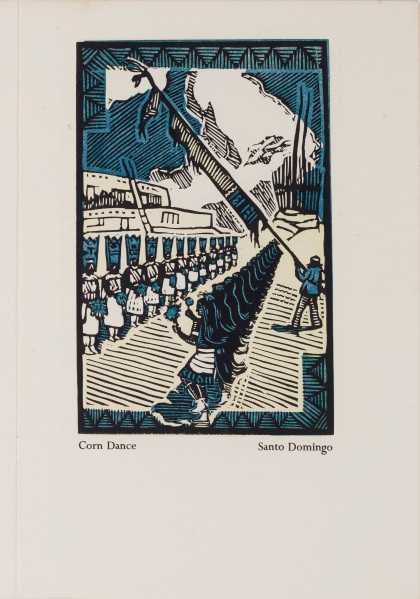

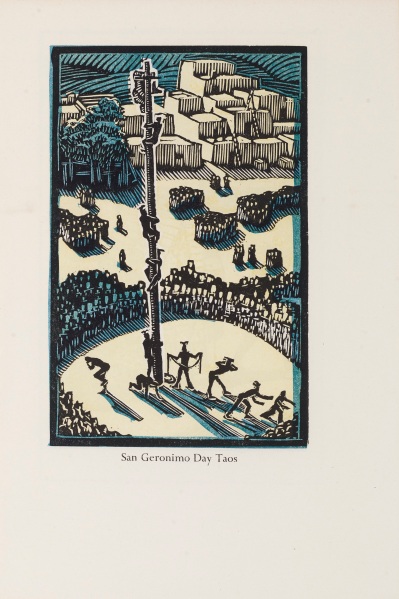

But changing cultural attitudes were given great political impetus when Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated President Herbert Hoover in November 1932 and appointed several individuals sympathetic to the Indians to positions of power. The curmudgeonly Harold Ickes was named Secretary of the Interior, the cantankerous crusader, John Collier was appointed commissioner of Indian Affairs, and the avowed Socialist lawyer, Felix Cohen was made the legal architect of the Indian New Deal. Even as the new commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Collier blocked Christian missionaries’ attempts to suppress native rituals and dances, Work Progress Administration (WPA) artists reinforced the shift in policy by producing prints for the Museum Extension Project designed to educate the nation’s youth and instill a sense of pride in America’s aboriginal culture and ceremonies.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Promised gift

Passage of the Johnson-O’Malley Act of 1934 enabled the federal government to provide education, medical services, and social welfare to Indians. With the able assistance of his anthropologist wife, Felix Cohen drafted the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act (or IRA). This piece of New Deal legislation allowed his boss, Harold Ickes to end the sale of allotments even as John Collier hit the brakes on the federal government’s “Americanization” programs aimed at eliminating Native American traditions. The IRA received an annual budget of $250k for organizing chartered corporations and tribal councils on Indian reservations and $10 million revolving credit to promote tribal economic development. Although far from perfect, the Indian Reorganization Act did conserve Indian land, soil, water, and stem the tide of communal land loss.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Promised gift

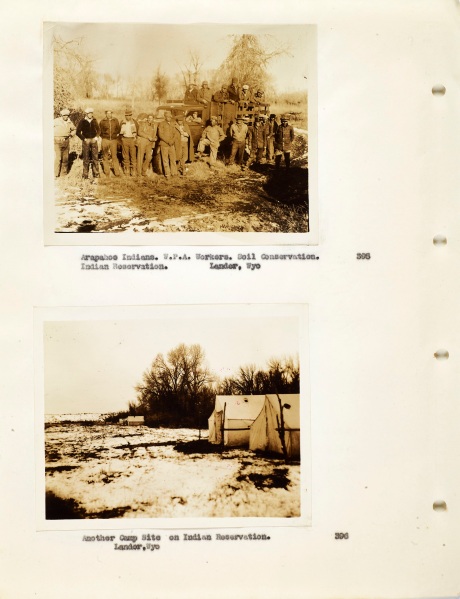

Given the dire crisis of the Depression, the first and most important goal of the Indian New Dealers was to provide work and subsistence for desperate native families. Towards that end, as many as 25,000 reservation Indians were recruited and enrolled by the Emergency Conservation Work Agency and found employment in 75 camps scattered across 15 western states. Other Indian youths whose parents were unemployed were enrolled in the Civilian Conservation Corps doing forestry work and earning wages sufficient to support their families.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Promised gift

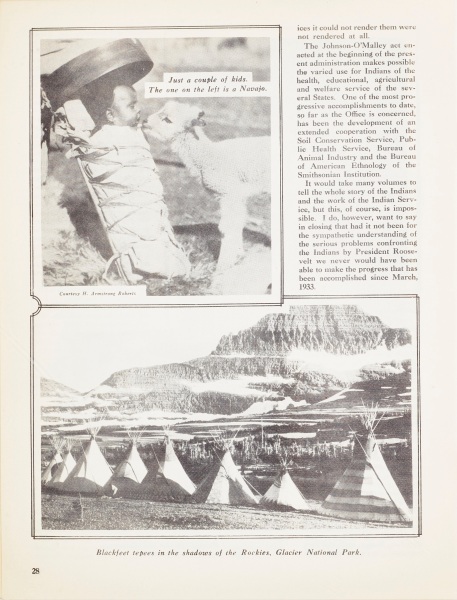

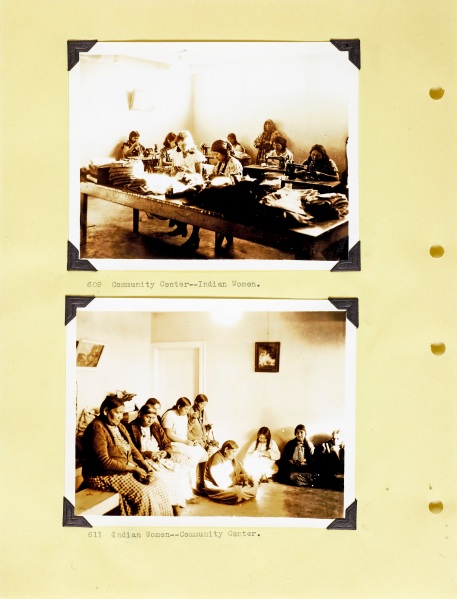

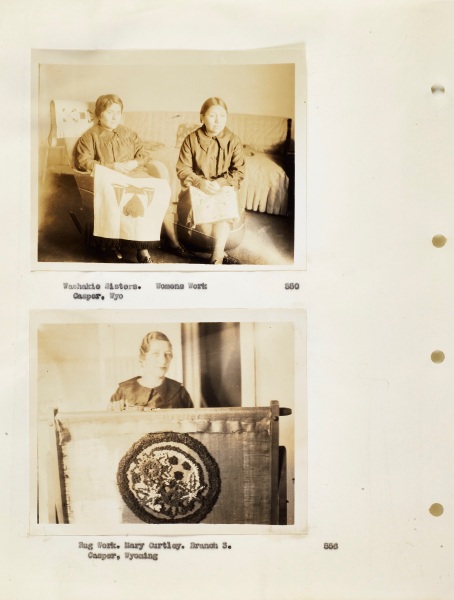

As commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Collier pushed to have Indians transferred from distant, Christian-run, boarding schools to local community day schools that encouraged bilingualism and promoted traditional Indian craftsmanship. The Wolfsonian Library holds more than three dozen Wyoming W.P.A. reports from the mid-1930s that document the federally funded projects in that state. Several of these reports include typed descriptions and photographs of reservation Indians who participated in and benefited from these federally subsidized projects. Many Indian men were employed in soil conservation work while Indian women worked in traditional carpet weaving and leather tanning projects aided by modern sewing machines.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

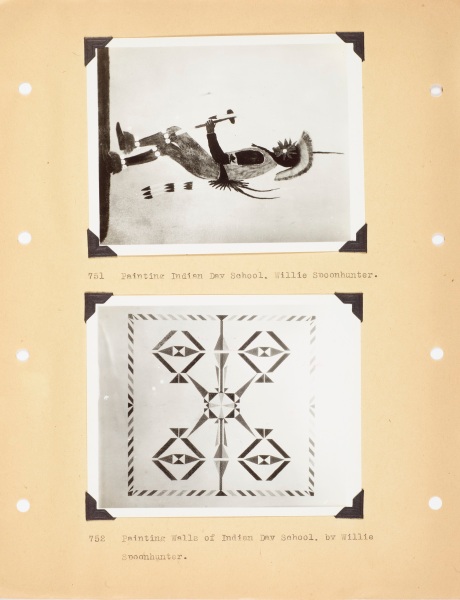

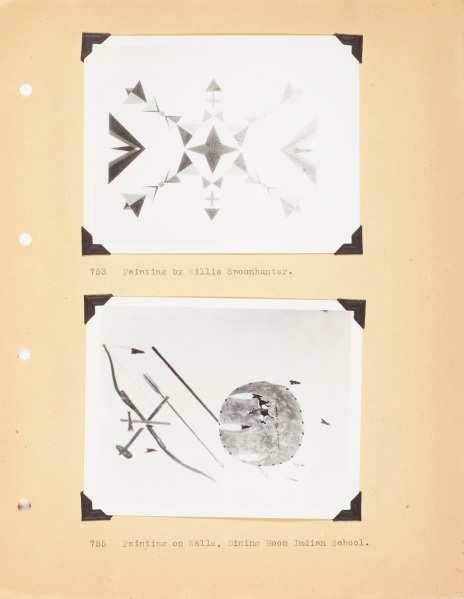

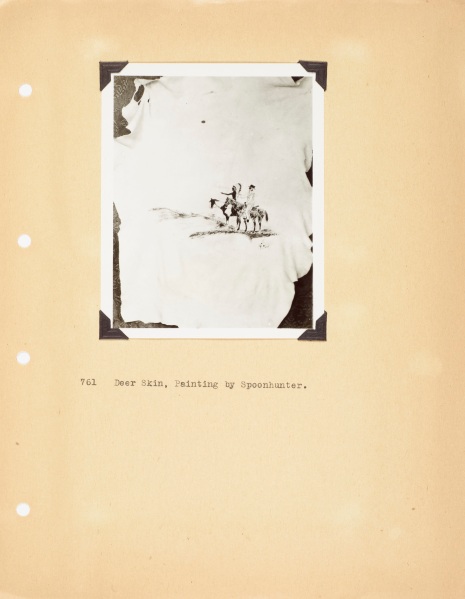

While the supervisor of the Federal Arts and Crafts project in Wyoming was too modest to claim any great contributions to the arts, he did note the discovery of Willie Spoonhunter, “an Indian lad on the Shoshone Reservation,” whose native abilities were added to the Arts Project. On a recent trip to the reserve, the WPA administrators were gratified to see several of the budding artist’s “Original Indian Designs” adorning the walls of the day school’s dining room. Photos provided in the report stressed that “Nothing in the way of a black and white photograph can do them justice since the colors used, true to the coloring of the West, lend a peculiar charm to the work.” The delegation even accepted a gift of one of Spoonhunter’s paintings rendered on a traditionally tanned deer skin.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

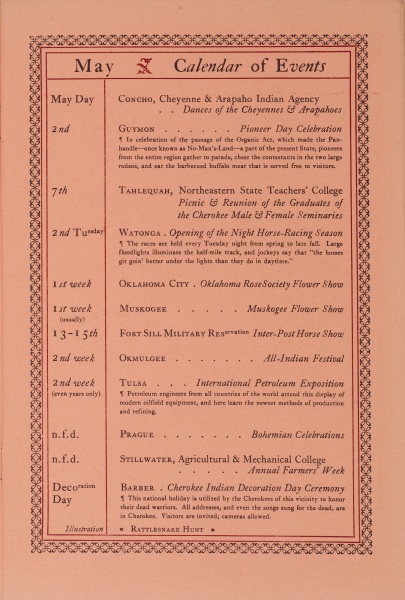

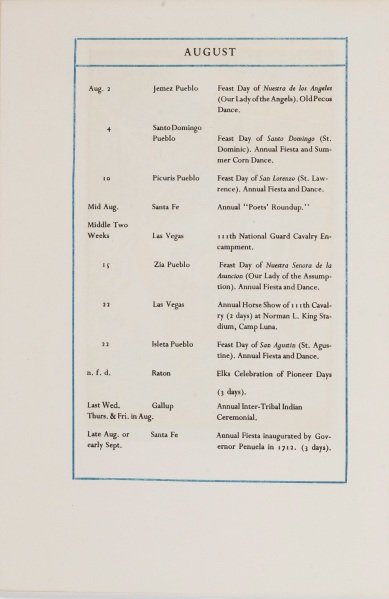

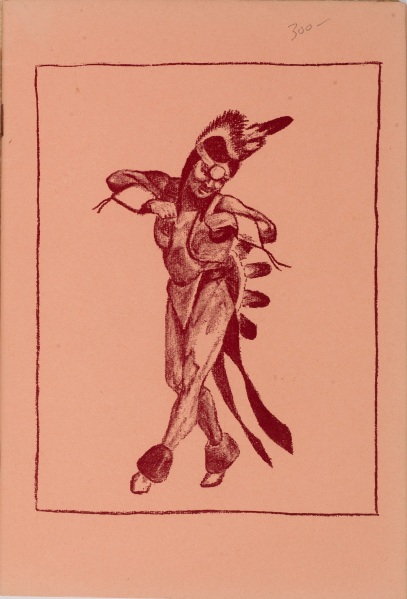

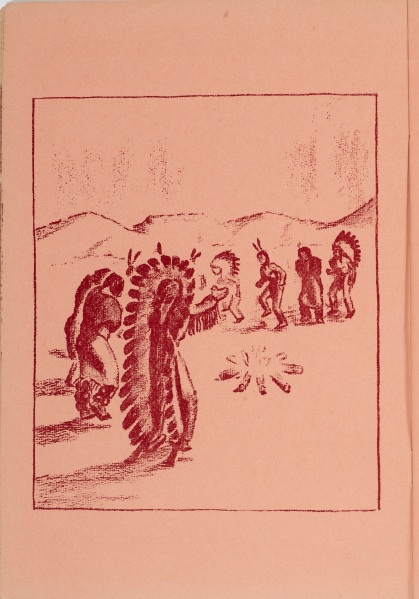

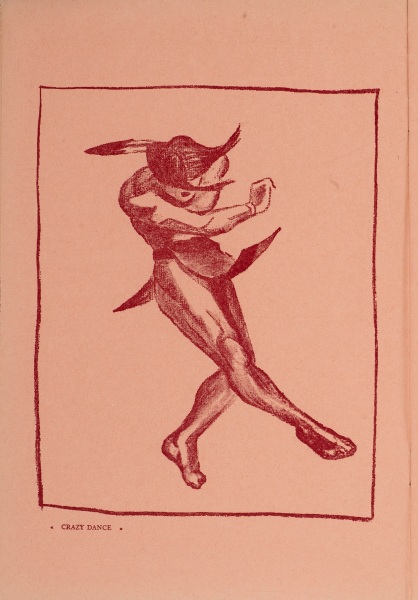

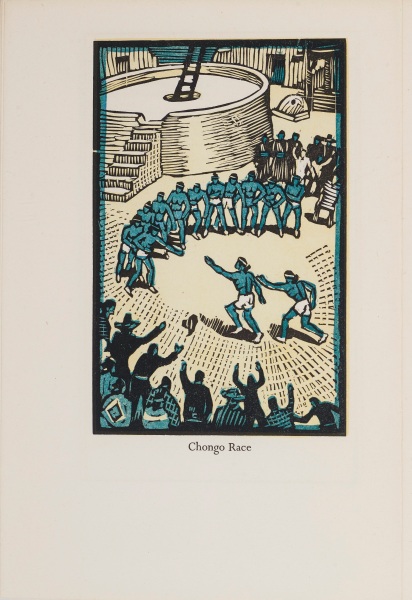

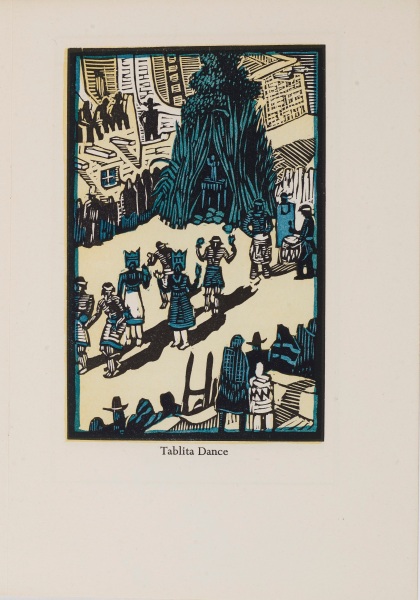

The radical change in federal Indian policies is also reflected in calendars published by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) aimed at promoting domestic tourism to stimulate the economies of Western states like Oklahoma and New Mexico. Whereas native dances and festivals had been demonized and suppressed by Christian missionaries in the 1920s, under the aegis of sympathetic New Deal administrators, such activities were actively encouraged. Taking advantage of a new climate of tolerance and interest in Native American culture, the WPA collaborated with local chambers of commerce to publish calendars of events compiled by Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) and illustrated by Federal Art Project (FAP) workers. While the fanciful illustrations rendered by FAP artists may or may not have faithfully represented such native dances, they certainly generated new interest in Indian customs once deemed “savage” but now recast as “exotic” and worthy of interest.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Promised gift

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

In addition to promoting pioneer days, square dances, fiestas, picnics, and rodeos, these calendars announced inter-tribal ceremonials, festivals, and costumed dances, with imaginative illustrations of the same.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Promised gift

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

Federal Writers’ Project workers also traveled across the country recording American folkloric traditions. As can be seen from the covers of a couple of Nebraska Folklore pamphlets, the compilers not only preserved pioneer tales and cowboy songs but also local Indian legends.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

Collier’s role in the New Deal for the Indian was the most far reaching and controversial. Citing the recognition of Indian citizenship, Collier argued that Constitutional guarantees of religious freedom applied to native peoples as well. Consequently, he forbade federal officers from requiring Indian attendance at Christian Churches, much to the chagrin of missionary groups. We should not overestimate Collier’s influence or assume that the New Deal completely upended decades of bureaucratic and paternalistic policy. The caption of a press photograph of new building construction in the Reno-Sparks Indian Village in January 1937 noted “How Administration, the Church and Education go hand in hand” as the Administration building, frame church, and new school were erected before any of the new single-room houses were built to accommodate the 250 native inhabitants.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Vincent J. Luca, Sr. Press Photo Collection

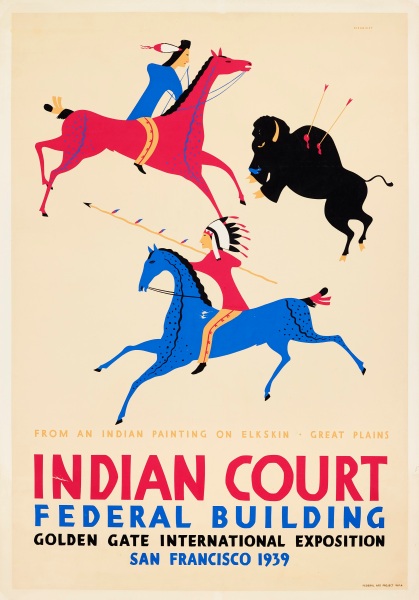

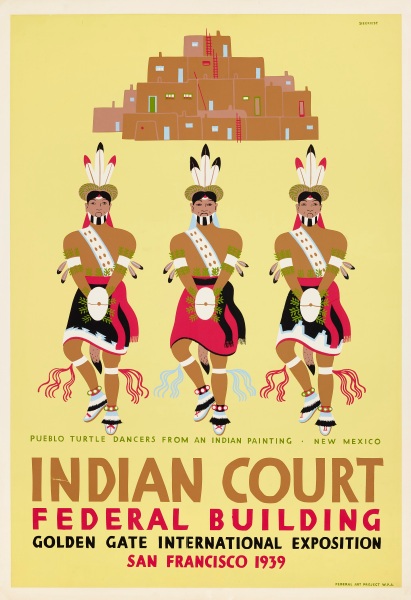

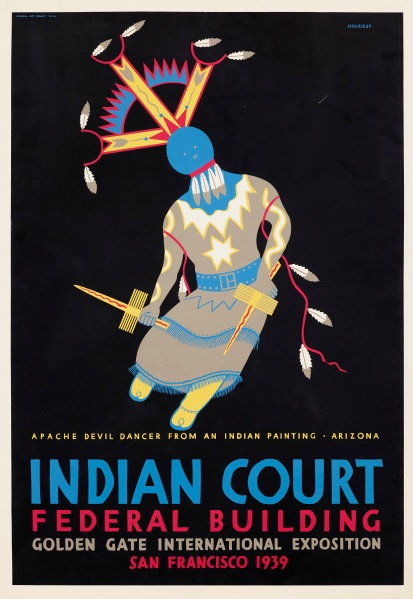

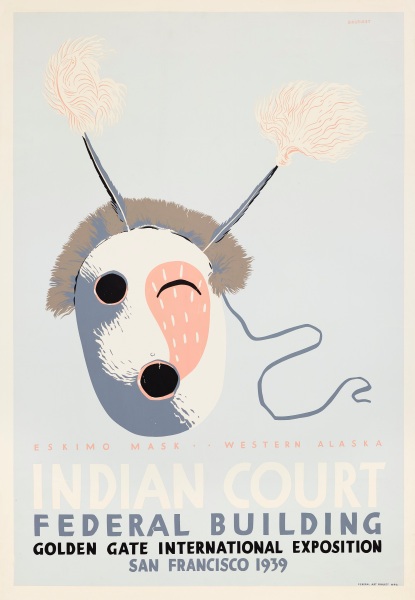

The New Deal ended in 1939 as unemployment evaporated as war clouds darkened European skies and American workers poured into factories as President Roosevelt put the nation on war-readiness status. But even as the Roosevelt Administration pivoted from “make work” jobs to making America the “arsenal of democracy,” the New Deal’s salutary impact on the American Indian grew rather than diminished. While Congress began defunding many New Deal programs, the federal government continued to promote Native American-inspired art. WPA posters and tribal art graced the walls of the Indian Court in the Federal Building erected for the Golden Gate International Exposition held in San Francisco from 1939 to 1940.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

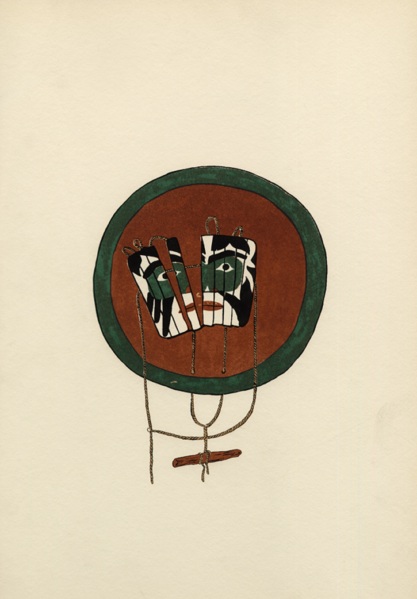

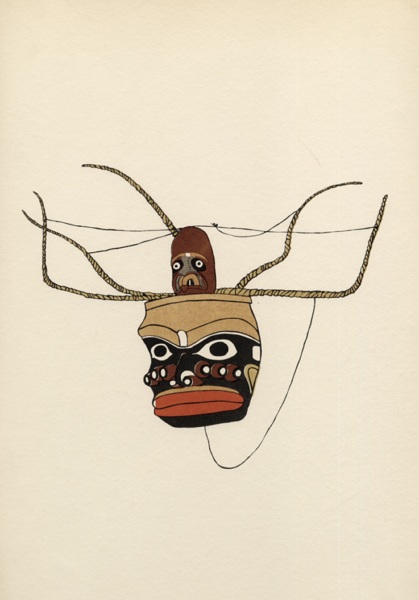

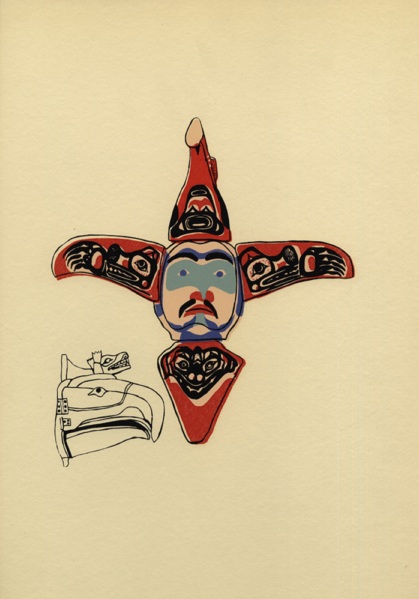

While the Federal Art Project’s Index of American Design focused its efforts on identifying and preserving Spanish colonial and Euro-American folk art traditions almost to the exclusion of artwork by American Indians, a project to create color illustrations of North Pacific Coast Indian masks begun under WPA auspices was completed and published by the Cranbrook Institute of Science in 1941.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

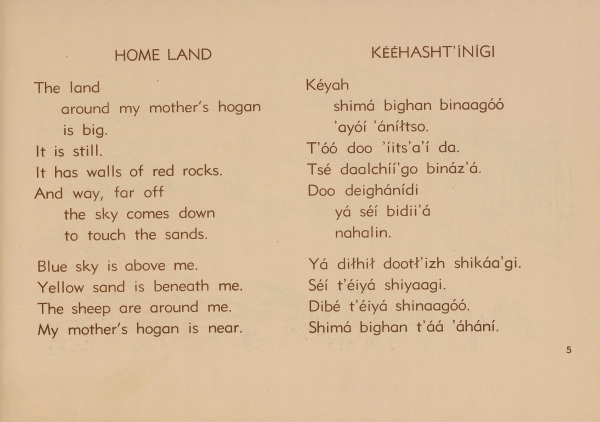

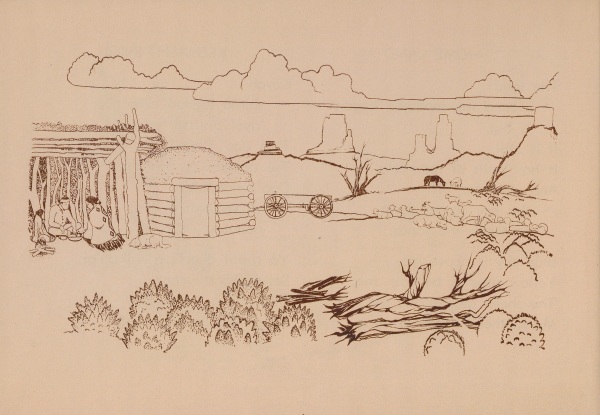

Another lasting product of the Indian New Deal was the government’s recognition that native languages and cultural traditions were worthy of preservation. Abandoning the earlier policy of shipping young Indians to boarding schools and forcing them to speak only in English, the Educational Division of the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs under Collier’s direction actively promoted bilingualism. The Educational Division even published children’s books for Navajo children with parallel texts in Navajo-English and employed a Navajo native, Hoke Denetsosie, as illustrator.

Ironically, the preservation of the Navajo language came just in time, as Navajo braves enlisted in the Armed Services during the Second World War, and a code derived from their ancient tongue helped keep the Japanese enemy in the dark during campaigns in the Pacific.