The Wolfsonian Library recently opened an installation titled: Tyrants and Terrorists: Satirists Bite Back. The exhibition includes nearly a dozen original late 20th century anti-Nazi cartoons drawn by Sam Gross, as well as some works from our own collection that lampooned Hitler and the Nazis as they rose to power and dragged the world into a Second World War. While brainstorming ideas for promoting the exhibition in social media, since Mr. Gross was such a prolific cartoonist and his archives could supply us with an endless stream of material, we though that we might try launching a site with a “Gag a Day.” Towards that end, I naively opened an Instagram account, uploaded a couple of images and a sentence of two of context, and sent it out into the web. Attempting to get back to the site the following day, I discovered to my surprise that the post had been taken down and my account had been suspended.

Over the next couple of days, I pondered where I might have gone wrong. My post, which admittedly included parodies of Hitler and Nazis, could not have been considered pro-Nazi or a form of hate speech by anyone actually examining the images or reading the brief descriptive text. Perhaps neo-Nazis might have been offended by the content, but that had not tied me up in knots.

Courtesy of Sam Gross

I could only guess from the swiftness of the act of suspension was that the post had not been flagged by a human censor, but rather had fallen afoul of some algorithm designed to detect and reject certain trigger words or images. I admit that I had probably been remiss in failing to carefully read the rules of the website before choosing a platform for promoting the installation. It is commendable (if also condescending) that a site would wish to protect its subscribers from hate speech, and vitriolic trolls in this age of extreme political partisanship and division. Upon reflection, I also became concerned about the free speech and censorship implications of someone, or more likely, some anonymous algorithm, determining what the public ought and ought not see and judge for themselves. The ultimate irony is that two of the three images I had attempted to post on Instagram dealt with satirists mocking Hitler and the Nazis for their penchant for censoring artists or dictating the content of their artwork.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

Ironically, one of the artists censored from public view by Instagram had courageously organized a one-man exhibition of anti-Fascist artwork in his native Copenhagen just days before Hitler and his army invaded the country, closed the show, and set the Gestapo on his trail. One of the paintings exhibited in that prematurely closed exhibition, Harakiri, attempted to warn his compatriots of the dangers of Nazi and Japanese military aggression which he feared was plunging the world into yet another suicidal world war.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

The painting is currently on display at The Wolfsonian museum in Plotting Power: Maps and the Modern Age, an exhibition organized by my colleague, Lea Nickless, focusing on how images of globes and maps were often turned into weapons of manipulation by commercial and political propagandists.

Today’s blog post on gags and gagging will consequently wrestle with the themes of cartoons and caricatures, and satire and censorship. Satire has for centuries, if not millennia, been a proven form of deflating the pretensions of autocratic and dictatorial regimes. During the First World War, many artists and cartoonists turned their talents to satire in the service of the war to ridicule the militaristic proclivities of the German Kaiser, Wilhelm II.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gifts of Francis Xavier Luca & Clara Helena Palacio Luca

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

While artists in the belligerent nations could be expected to provide propaganda aimed at the enemy, even cartoonists in neutral nations shaped public opinion about the war. Greatly incensed by Germany’s invasion and occupation of neutral Belgium and other wartime atrocities, the Dutch cartoonist, Louis Raemaekers penned hundreds of cartoons critical of the Kaiser and the war that he unleashed, and had a price put on his head for doing so. Some of his artwork also graces the gallery of the Plotting Power exhibition at The Wolfsonian, while other of his influential editorial cartoons mocking the Kaiser, the Crown Prince, and Germany’s macabre “dance of death” were republished after the war in voluminous tomes.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

Satirists and cartoonists did not put down their pens after the First World War ended. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, caricature evolved in Cuba as an important means of promoting culture and attacking social ills and political corruption. Artists such as Conrado W. Massaguer, Hercar, Juan David, Arroyito, and others penned and published tens of thousands of biting satires of politicians, frequently enduring arrest and jail time, and even risking death threats and force exile. When Cuban President Gerardo Machado decided to remain in office for another term and to dispatch paramilitary thugs to silence his enemies, Massaguer published several critical cartoons that irked the thin-skinned president so much so that the publisher and cartoonist was forced to flee the country for his life as his popular publications were suppressed and temporarily shut down.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Promised gift of Vicki Gold Levi

Some non-political artwork of Massaguer is on display in Turn the Beat Around, a Wolfsonian exhibition focusing on Afro-Cuban music and its impact on the American dance music scene from the 1930s through the 1970s and beyond. Many of Massaguer’s cartoonist colleagues suffered similar experiences after Fulgencio Batista ruled Cuba from behind the scenes after the overthrow of President Machado in 1933.

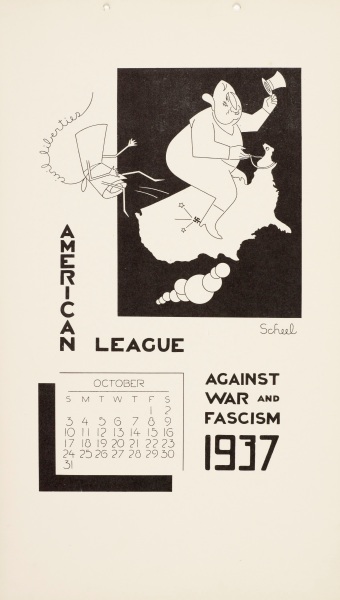

Cartoonists were especially active during the era of the Great Depression, heaping scorn on the capitalists deemed responsible or to the political opportunists who took advantage of the economic crisis to scramble to power. Left-leaning artists like Hugo Gellert ridiculed capitalists such as J. P. Morgan, conservative media moguls such as William Randolph Hearst, right-wing radio pundits like the “Radio Priest” Charles Coughlin, as well as presidential aspirants like Huey P. Long of Louisiana whose campaign song promised to make “Every Man a King.”

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Francis Xavier Luca & Clara Helena Palacio Luca

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Francis Xavier Luca & Clara Helena Palacio Luca

Other members of the Communist Party faithful also attacked Hearst for accepting money from the Nazis in return for no longer publishing critical editorials of Hitler and his henchmen and trampling on Americans’ civil liberties.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Francis Xavier Luca & Clara Helena Palacio Luca

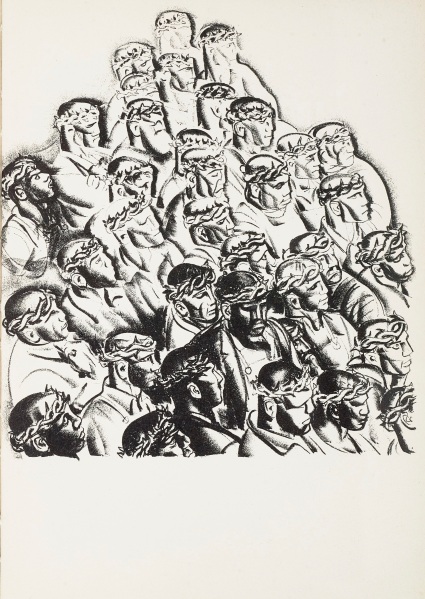

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of August Mecklem Estate

Even if coming from a source that many Americans disliked and distrusted, such critical cartoons provided an important counterbalance to the slanted news promulgated by Hearst and his media empire and challenged Americans to educate themselves and to form their own opinions.

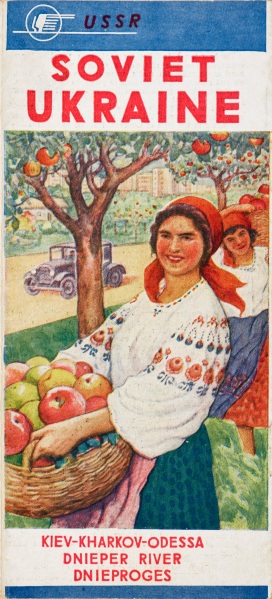

Too many on the left remained dangerously quiet on the disquieting realities in the Russian Worker’s Paradise, where millions of Ukrainian peasants were deliberately starved to death by Stalin. There is an irony that can be derived from viewing Soviet propaganda posters and pamphlets of the era today (on view in The Wolfsonian Plotting Power exhibition), which ludicrously lauded the collectivization of the farmland that brought on the politically motivated famine.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Audrey Feldman

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

In France, the artist Paul Iribe penned many cartoons equally critical of the Communists, Socialists, and National Socialists he deemed to be the greatest threat and danger to French liberty. As Hitler repudiated the disarmament dictates set out in the Treaty of Versailles, Iribe ridiculed English Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain’s attempts to appease Hitler, picturing the latter in drag and a blond wig as a means of lampooning the brunette leader of the blond master race!

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

Other French cartoonists also weighed in on the type of justice to be expected under Stalin’s dictatorship of the proletariat.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

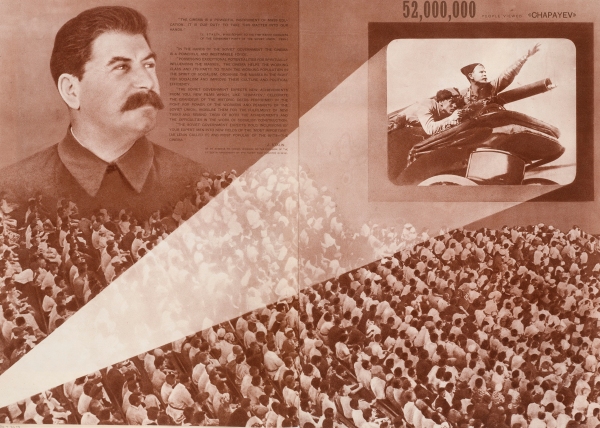

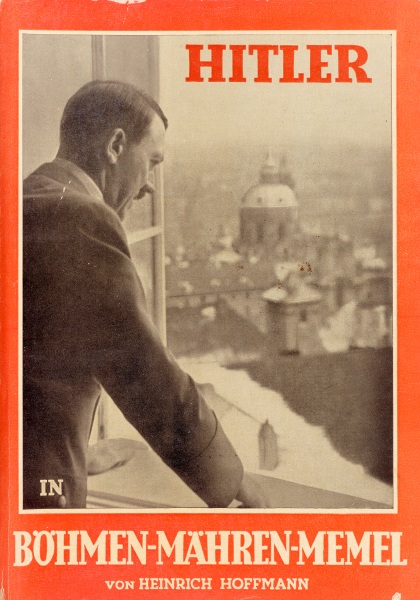

The modern totalitarian regimes of the Fascists, Nazis, and Communists perverted the relatively new medium of photography and cinema to promote positive images of life under their “benevolent” dictatorships.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

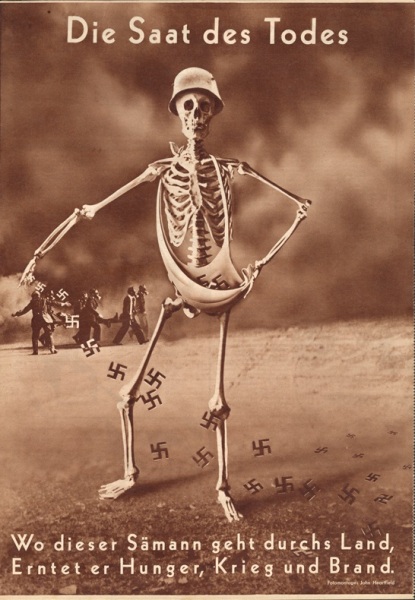

Before the advent of computer software and Photoshop, critics such as John Heartfield hand cut and pasted some of those staged images to create photographic collages (or photo-montages) that hinted at the sordid reality beneath the gelatin silver prints published by Nazi propagandists.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

Similarly, caricaturists and cartoonists used their pens and their imagination to similarly ridicule dangerous demagogues and would-be tyrants. The Mexican ethnographer and artist, Miguel Covarrubias, for example, helped shape public opinion when his irreverent lampoon of Fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini graced the cover of the popular American magazine, Vanity Fair.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

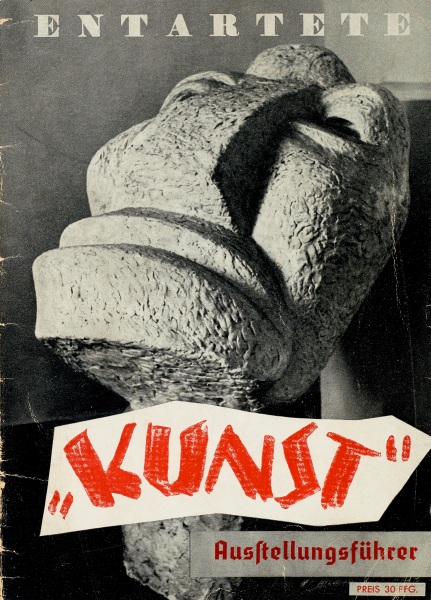

After seizing power in Germany, Nazis burned books, hindered people from seeing films they disliked, discouraged people from listening to Jazz music, and organized exhibitions dictating what constituted “good” versus “degenerate” art.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Mitchell Wolfson, Jr. Collection

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Michael Rosenfeld

But despite Nazi attempts to ban artwork and censor content they didn’t like, freedom-loving cartoonists hammered away at Nazi ideology and repression, especially after Hitler’s armies began invading and occupying neighboring nations. At great peril, artists in Nazi-occupied territories let the world know what they thought about Hitler, with Dutch and Danish artists transforming Der Führer into a ghoulish skull or reinterpreting Hans Christian Anderson’s The Evil Prince into an anti-Hitler children’s propaganda book.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Purchase, Collectors’ Council Fund

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Pamela K. Harer

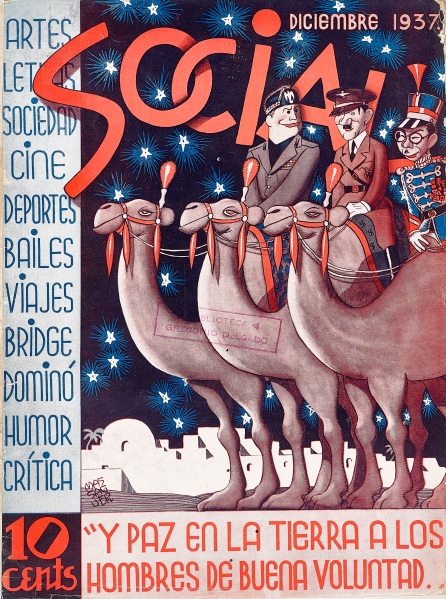

Even in the Western Hemisphere, cartoonists attacked Hitler and the Axis Powers on the covers of popular magazines.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gifts of Francis Xavier Luca & Clara Helena Palacio Luca

When the Second World War ended and ushered in the Cold War, there were elements in America who, well before the era of McCarthyism, pushed legislation designed to outlaw the publication of materials deemed communistic. Far from suppressing such sentiment, such misguided acts provided these groups with a legitimate First Amendment grievance which they used to rally support for their cause.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Francis Xavier Luca & Clara Helena Palacio Luca

Perhaps we might learn from such mistakes in the past. Rather than providing undemocratic hate groups with a legitimate First Amendment grievance, maybe we should allow them to rant and vent their views but encourage the Late Night satirists (like Jordan Klepper) and cartoonists (like Sam Gross) to ridicule, debunk, and deride their odious ideas and crazy conspiracy theories.

The Wolfsonian–FIU, Gift of Leonard A. Lauder